Bożena Kisiel, Retired Psychologist

From 1941 - 44 my father was a soldier in the Polish resistance Home Army [also known as Armia Krajowa or AK]. In Gdańsk, as a Home Army soldier coming from the Vilnius region, he was closely watched by the Russian security service. I only recently learned about this from a book that was written a few years ago. In fact, I learned many things about my father from this book, including that he was bugged. There was one phone on our street. When it would ring and my father would take the call he would sing in Russian. “A green maple plays with a cheerful leaf, under the maple we both play, you and me. Hello there, this is Kisiel.” I always wondered why he was singing as I was a child and did not understand what he was doing. Only now, years later, did I learn that he knew about the wiretap and he sang to that listener carefully.

In 1944 my father, as a commander of one of the AK brigades in the Vilnius district, was deported to Siberia by the authorities of the Soviet Union. He returned to Gdańsk at the end of 1947. I met him for the first time when I was four years old. He did not hide that he was a former Home Army soldier and he never hid his negative attitude towards the Soviet Union. He worked for the Port Authority and because of his AK past and suspicions that he and other colleagues originally from the Vilnius region were doing some anti-Polish activity, he could never get a promotion. Out of 6000 employees he was one of the few who did not belong to the Communist Party or to the Society of Polish-Soviet Friendship. My brother, who graduated from maritime school, couldn't sail on fishing vessels that called on ports because of my father’s activities.

Recently, I got a CD with recordings of my father from the Institute of National Remembrance. On it were recordings of his conversations that were bugged. For example, an entire dialog of my father saying goodbye to a fellow soldier and friend at a funeral. With all of these conversations, everything was recorded accurately, his language, his behavior when talking, everything is there. What was true in the text though, it is difficult to say. For example, I read that my father’s closest friend, who visited our house regularly, was informing on him. My father was the godfather of his daughter and I don't really believe that his friend was a spy. Maybe his friend was blackmailed by the Secret Police. Or maybe my father and his friend made an agreement and specific information that was pre-planned was given to the authorities.

In Gdańsk over 25% of the people have roots in the Eastern Borderlands, including the Vilnius Region. My parents and their generation had a well-established sense of identity. They were highly educated and brought a lot to Gdańsk. They had a great influence on what was happening in this city in terms of their thinking, their attitude, their enormous negative experience with Russia and their willingness to fight for freedom.

As I think of myself and other people from my generation we were searching for our identity and we were willing to do something for this city to show our moral right to be a Gdańsk inhabitant. That is why many of these people were involved in Solidarity and the strikes at the shipyards. When Solidarity was established, all of the members focused on the work. In August 1980 you could feel that people knew that something big was at stake and that its success depended upon us.

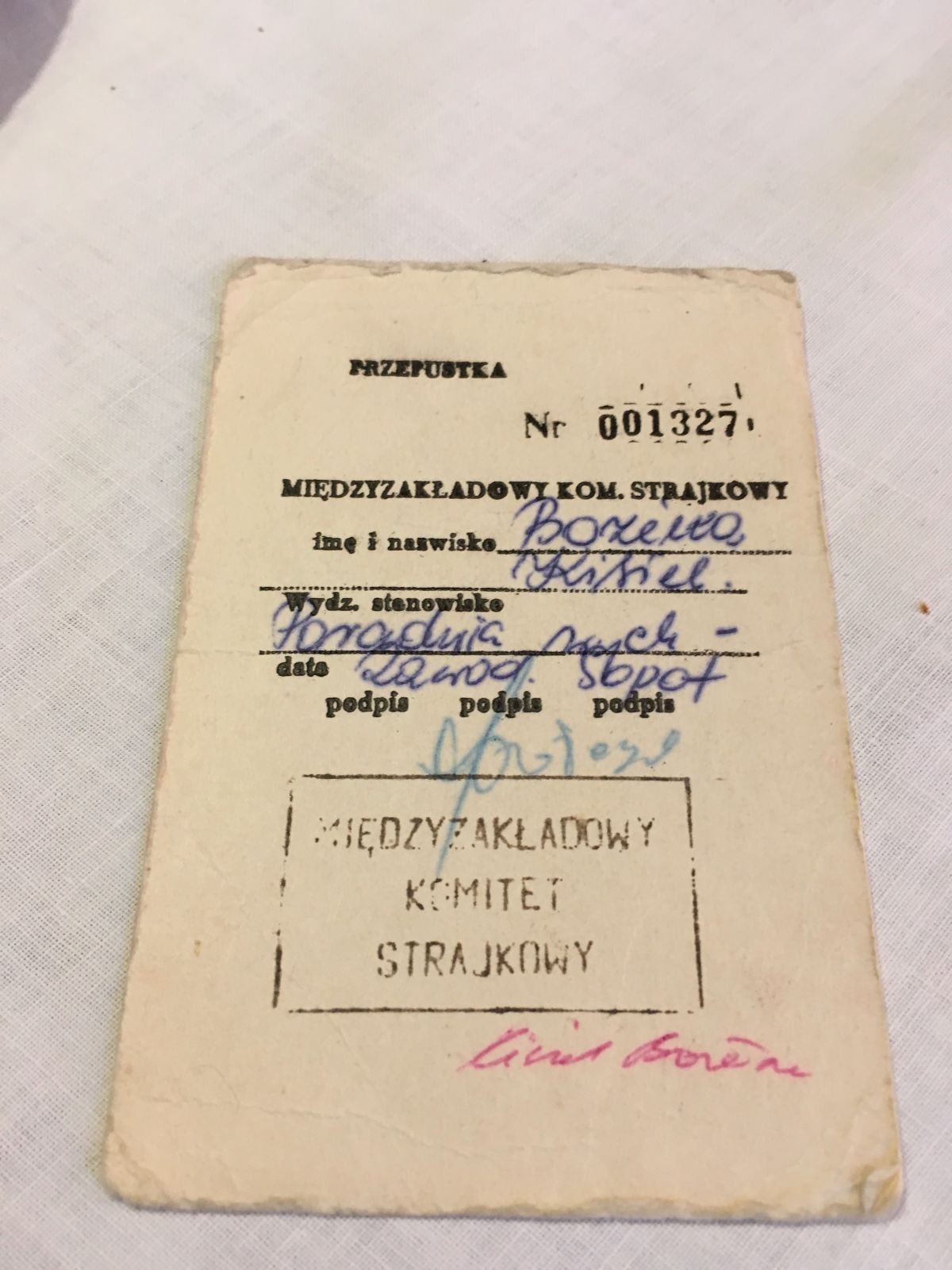

When the strike broke out in August 1980, I gathered all the employees of the clinic where I worked, proposing that we support the strike. Apart from one person, they all agreed. We went to the shipyard and gave our written support to the strike with our signatures. I stayed there until the end of the strike as the representative of the educational and professional counseling center on behalf of my colleagues who returned home. Some people did not leave the shipyard at all during the strike. In order to enter the shipyard, passes were needed at all. We had passes to out in the evening and return in the morning.

Pass signed by Lech Wałęsa to leave the shipyard strike at night and return in the morning

One time when a group of us were sitting in the shipyard's Health and Safety Hall waiting for Prime Minister Mieczysław Jagielsky to return from Warsaw, it suddenly occurred to me that we do not have any propositions of statutes or principles written down on which we based the movement. So we took a piece of paper and Mariusz Muskat and Bogdan Borusewicz and wrote right then and there the postulates concerning the establishment of Free Trade Unions. I still have the original document at my house.

When Martial Law started in Poland, I was working here in Sopot at an orphanage. I was the second person in charge after the headmaster of the orphanage. When I heard the General of the Army, Wojciech Jaruzelski declare war on the people I went straight to the orphanage to make sure that the child were okay. [In Poland, Martial Law is referred to as civil war as the Army invoked powers for itself that were reserved for wartime.] It was a Sunday so there were not so many staff members working, but when I got there all of the staff had come to check on the well—being of the children, to see that they were not frightened. I have enormous respect for these people to have left their own families to check on the children.

Because I worked at the orphanage I had passage permits and could commute to and from the kindergarten during the curfew. One time I came home and I saw the secret police in front of my house. And I as I knew my neighbors, they the police would only for me and not for my neighbors. I snuck around the building and went through the back door. My mother was home and I could hear the conversation between her and the Secret Police. In front of the door is a military man and the secret police and my mother is on the other side of the door saying, “How the hell do I know where she is, she is wandering the city by night, I don’t know where she is.” Finally, after they gave up and left, I came into the house and there was my mother sitting in such a way and smoking a cigarette. It came to me that she just felt as she had during the Russian occupation when she was investigated. She would be called to the Secret Police office and where they would speak to her in Russian. Even though she spoke fluent Russian, she would ask for a translator so they would not know that she understood what they were saying. One time the investigator said to my mother do not tell anyone that you have been here. She told him that it was too late and that she had already said goodbye to her friends. “Why,” he asked her “have you said goodbye to all of your friend?’ And she told him that she knew that there was a good chance that she would never come back from them. But she came back and continued to be strong and hold to her beliefs. That was her generation’s Spirit.

Now I run an organization called Towarzystwo Miłośników Ziemi Wileńskiej (Vilnius Land Lovers Society), Pomeranian Branch. One of the motives of my work and many of the projects I do is to show the role of people who came from the Vilnius region in the development of Gdańsk in the past decades. The current generation whose grandparents or great grandparents came from the Vilnius region are curious about their heritage and roots. So I invite them to participate in various projects so that they learn this history and know where it is that they come from. For me, this is the most important work right now, not to forget our history and the people, like my father, who fought for freedom.

This conversation was in Polish with the aid of a translator

Photos by Janeil Engelstad